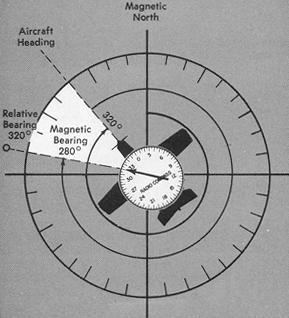

The measurement of relative bearings of other vessels and objects in movement is useful to the navigator in avoiding the danger of collision. The measurement of relative bearings of fixed landmarks and other navigational aids is useful for the navigator because this information can be used on the nautical chart together with simple geometrical techniques to aid in determining the position of the vessel and/or its speed, course, etc. By contrast, Compass bearings have a varying error factor at differing locations about the globe, and are less reliable than the compensated or true bearings. Relative bearings then serve as the baseline data for converting relative directional data into true bearings (N-S-E-W, relative to the Earth's true geography). The United States Navy operates a special range off Puerto Rico and another on the west coast to perform such systems integration. Since World War II, relative bearings of such diverse point sources have been and are calibrated carefully to one another. The relative bearing is measured with a pelorus or other optical and electronic aids to navigation such as a periscope, sonar system, and radar systems. The following images show how to simply calculate the Bearing.In nautical navigation the relative bearing of an object is the clockwise angle in degrees from the heading of the vessel to a straight line drawn from the observation station on the vessel to the object. The crew can eyeball it from the Electronic Countermeasures Display (ECMD), the Bearing Distance Heading Indicator (BDHI) or calculate it by means of the readings provided by the TID, by combining the values of HDG and RBRG. There are a number of way to approximate or calculate the Bearing. The Relative Bearing is useful to perform minor adjustments and give indications to the pilot because it gives the direction (0 This reading is, however, not the common bearing used, for instance, in a BRAA call. The TID is capable of displaying the Bearing to a hooked contact.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)